Michelangelo Buonarotti

Pieta

Marble sculpture

Pieta means only one thing to many art lovers: Michelangelo Buonarotti's sculpture of the Virgin Mary holding the body of Christ. This was the first great work of art I ever saw, and the setting left an indelible impression on a 12-year-old boy from a religious community suspicious of sacred images. I was one of 27 million visitors who passed by Pieta on a mobile walkway in the Vatican Pavilion at the 1964-1965 New York World’s Fair. I have seen the Michelangelo masterpiece several times since then in St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome but never with the same rapture of that first fleeting glimpse, when the sculpture’s polished marble surface gleamed under garlands of dark blue votive lights.

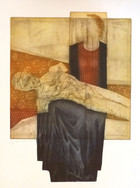

Michelangelo was only 24, when he completed Pieta in 1499. The Carrara marble statue, measuring 174 x 195 cm., was commissioned as a funeral monument by Cardinal Jean Bilheres de Lagraulas, the French royal envoy to the Vatican. It was immediately hailed as a work of genius, exemplifying Renaissance ideals of physical perfection. The marks of the Passion are barely noticeable on Christ’s beautifully modeled body, as if he has fallen into a deep sleep. The grieving Mary looks far too young to be the mother of the dead Savior, but as Michelangelo explained, women who are pure in soul and body never age--and of all woman, the Virgin Mother would have resisted the ravages of time.

The Florentine sculptor found an ingenious solution to a problem, facing all artists who take on the sacred theme of Pieta: how to depict a woman holding the full-length body of a man in her lap. Michelangelo presents the two figures in a pyramidal composition. The Virgin Mary’s head is at the apex of the triangle, looking like a carved portrait on a mountain peak, while her legs (which would have to be disproportionately large to hold the weight of Christ’s body) are concealed in the sinuous folds of drapery, filling out the base. The figure of Christ has also been downsized to fit into the contours of Mary’s lap. Our eyes are easily fooled by this artful deception.

Pieta means “pity” or "compassion” in Italian, but this sculptural motif originated in German-speaking regions of Europe around 1300, where the image of Mary holding the dead Christ was known as Vesperbild (Vespers image), after the evening prayer in the Church’s Liturgy of the Hours, associated with the deposition of Christ’s body from the Cross. Pieta is really a two-figure variation on traditional iconographic imagery of the Lamentation of Christ, where Mary grieves over the body of her son alongside other mourners at Golgotha. It became one of the most popular devotional images in Northern Europe in the late Middle Ages .

Like all great cultural icons, Michelangelo’s Pieta has been admired and mocked; copied and parodied; even damaged in 1972 by a hammer-wielding attacker, claiming to be Jesus Christ, who broke off a large part of Mary’s left arm and a chunk of her nose, also chipping the left eye and the veil. The importance of Pieta in sacred art is too broad a theme to be discussed in a short essay, but I have singled out fourteen pieces from the Sacred Art Pilgrim collection, which pay homage to the Michelangelo masterwork and offer interesting variations on a theme, which has added rich emotional layering to the brutal, male-dominated imagery of the Passion of Christ by introducing the archetypal figure of the mother in mourning.

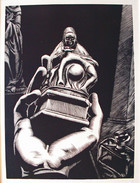

Pieta meets pop culture in the Italian-language version of the poster for South Korean Director Kim Ki-duk’s film, Pieta, which won the Gold Lion at the 2012 Venice International Film Festival. The leading actors in this drama of a middle-aged woman and underworld thug who may (or may not) be mother and son pose in a living tableau of the Michelangelo masterwork. American Illustrator David Levine offers another “quotation” of Pieta in his caricature, Mother and Child, from The New York Review of Books, where Mary looks down in consternation at the cubist stone block in her lap. In Austrian Printmaker Louis Hechenbleikner’s enigmatic woodcut, a hand thrusts a Pieta statuette past a wine cruet into a black void, where we glimpse the drapery of another holy figure.

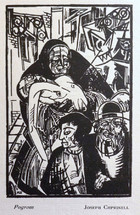

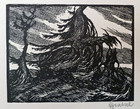

Just suggesting the form and outline of Pieta can add emotive power to images, set in completely different contexts. In his wood engraving, Pogrom, Central European Artist Joseph Chprinell replicates the posture of the slain Christ in the fallen head and arm of the naked body the old woman clasps to her breast, a victim of anti-Semitic violence. Czech Printmaker Arnost Hrabel turns fallen tree trunks into an image of Mary and the dead Christ in his 1920s woodcut of a devastated forest. Scottish Artist Angus Ogilvy offers a more ambivalent variation on the theme in his garishly-colored, giclee print, which might depict a mother mourning her dead son out on the mean streets in front of brightly lit shop windows with fashion mannequins.

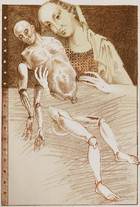

Not all Pieta-makers are drawn to the coldly polished perfection of Michelangelo’s work. Sculptor Ossip Zadkine, who was born in Vitebsk, Russia, and settled in France, has created an almost three-dimensional lithographic rendering of Pieta, where the broken body and exposed ribs of Christ harken back to German Vespers images. New Mexican Artist Marie Romero Cash emphasizes maternal love in her painted, gessoed-wood bulto (sculpture), made in the traditional style of the saint-makers of the American Southwest, where Mary tenderly presses her face against the cheek of her dead son, whose body is enfolded in her all-encompassing mantle. The crudely-hewn features of the Virgin Mother in Polish Folk Artist D. Gruszczynski's tightly compressed figure study in carved wood suggest anger more than pity or compassion.

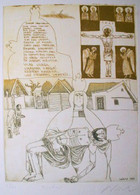

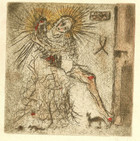

The motif of the grieving Mother of Christ has special resonance for artists in Eastern Europe and the nations of the old Soviet Empire. Lithuanian Printmaker Antanas Kmieliauskas creates a powerful Mary, who is an emblem of his suffering motherland in the turbulent 20th century, her heart pierced with the swords of the Virgin’s Seven Sorrows (the prophecy of Simeon, the Flight into Egypt, the loss of the Christ Child in the Temple, and Stations of the Cross IV, XII, XIII, XIV). Vignettes to the side of the central image show Communist-era deportations to Siberia and a map of Russia with crosses marking camps in the Gulag. Hungarian Illustrator Adam Wurtz shows a village Pieta in his etching along with the 13th century text of Omagyar Maria-Siralom (Old Hungarian Lament of Mary), the oldest written poem in the Hungarian language. Note the vigilant angel with the milk can!

Bohuslav Reynek was a Roman Catholic contemplative poet and printmaker from Bohemia, who also revealed mystical moments hidden in everyday scenes. His Pieta is set down on the farm, where a mouse finds shelter from a cat in the folds of the Virgin Mary’s robe. Jan Kavan, another Czech graphic artist, is represented by a lithograph and an etching, showing Mary cradling a figure, who is both man and child at the same time. The prints bring out a key theological point implicit in all Pieta imagery. The Virgin Mary holds the body of her crucified son in her lap just as she once cradled the infant Jesus. The message of Easter begins with the Christmas Story. The Christ Child was born to die, his body broken to redeem humankind.