Survey the Wondrous Cross

The Cross is the most readily recognized symbol on the planet. We see it so often, depicted in works of art, displayed in books and on billboards, used in decoration, worn as a fashion accessory, it is in danger of losing its meaning. This meditation (using my own artwork) considers the image of the cross as a symbol, a historical sign, and a witness to faith. As you read these texts, take a moment, in the words of the great 18th century hymn writer Isaac Watts, to “survey the wondrous Cross.”

The Wondrous Cross. Consider the Cross just as an abstract form. In its simplest reading, the Cross can be viewed as a “plus” sign, adding to life, not subtracting. The vertical line, reaching from earth to heaven, represents a link between God and humanity. The horizontal line suggests a bond, connecting one person with another. Its shape recalls a human figure with arms outstretched, giving, embracing. What associations does the sign of the Cross have for you?

The Old Rugged Cross. For Christians, the Cross is more than just an identifying logo. It refers to a specific historical event in 1st Century Palestine: the execution of Jesus of Nazareth, nailed hands and feet to wooden crossbars. As the familiar hymn goes, “On a hill far away stood an old rugged cross/The emblem of suffering and shame.” We tend to forget how shocking images of the Crucifixion must have been for early Christians, who had the same feelings about the Cross we now have for the electric chair. I conceived of this piece as an abstract study, showing a red cross against a chaotically-patterned background (a paint-spattered, old vinyl table cloth, I once used in my work area!) The color of the Cross proved too dark, so, I began experimenting with lighter shades, impatiently repainting it until the surface of the cardboard began to warp and shred apart, revealing the original deep red layer underneath. The effect was visually unsettling, recalling torn human flesh. I was tempted to start again but decided to leave the shape just as is. Images of the Cross ought to disturb us.

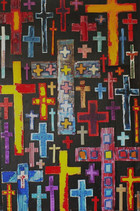

The Apostle Paul writes in Galatians 2:19-20 (NIV): “I have been crucified with Christ and I no longer live, but Christ lives in me.” In His Image explores the mysterious way believers share in Christ’s Crucifixion and Resurrection, as we are “being transformed into his likeness with ever-increasing glory (2 Corinthians 3:18, NIV)." The crosses in this collage have arms of equal length and width, but this uniform shape comes in 25 variations. Some are cut-out crosses. Others are just cross-shaped holes in cardboard squares. All are of different colors, set on a variegated, multi-textured background. This diversity in unity reflects the experience of spiritual transformation, as believers conform to Christ’s likeness, each in their own way.

Still Life. As the title implies, this is a study of real objects: a brightly painted wooden crucifix from Honduras, placed among stones, gathered from beaches on the island of Cyprus. Yet, we don’t view this painted panel as we would an ordinary still-life, say, of artfully arranged fruit in a china bowl. Such is the power of cross imagery and its many associations that seeing these objects, we recall the Passion story: the hill of Golgotha and the Crucifixion; Christ, rising from the tomb, carved out from rock.

Keep thinking of wood and stones as you study this next piece. Road to Golgotha is an abstract collage of color-pencil drawings, pebbles, and corrugated cardboard, inspired by a visit to Jerusalem and a walk along the Via Dolorosa, the route Christ is supposed to have followed on the way to his Crucifixion. The drawings show graffiti left by pilgrims to the Holy City. The stones recall the rugged terrain of Golgotha. The cardboard suggests the wood of the Cross. Reflect on the Crucifixion as an event taking place in real time, when as Theologian Francis Schaeffer once put it, “you could have reached out to touch the cross and picked up a splinter in your finger.”

Pilgrimage to the Holy Land was a dangerous and costly enterprise in the Middle Ages, so, Christians in Europe did the next best thing--they began acting out Christ’s walk to his Crucifixion in their home churches, a meditative exercise, remembered in Stations of the Cross. Christ is tried by Pilate and given his cross, stumbling for the first time, as he makes his way to Golgotha. He encounters his mother, Mary; gets help to bear the Cross from Simon of Cyrene; leaves Veronica an image of his holy face on a cloth; stumbles a second time; speaks to the women of Jerusalem; and stumbles a third time, before he is stripped of his clothes and nailed to the Cross. After Christ is taken down from the cross and buried, I have added a fifteenth image, recalling the Resurrection. Starting at the last panel at the bottom left, make a pilgrimage with your eyes, along the Via Dolorosa, turning left down the central row, proceeding right along the top tier until you reach the golden Cross in the empty tomb.

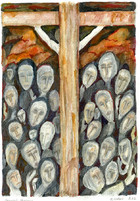

Just shifting your point of view can reveal something new in the old and familiar. The next set of images present the traditional Crucifixion scene from three different perspectives. Beneath the Cross is modeled on medieval European paintings of Christ’s death, where wealthy patrons paid artists to portray them, kneeling at the foot of the Cross in positions usually reserved for the Virgin Mary and St. John. It was, no doubt, a form of self-advertisement but also reflected a new type of piety, in which believers were drawn to the humanity of Christ and sought to identify in some personal way with his physical sufferings. Ethiopian Crucifixion reminds us of the universality of the Crucifixion story, depicted, here, with the bright color palette and symbolism of Ethiopian Orthodox iconography. Spanish Passion places you above and behind the Cross, giving an overview of faces in the crowd: indignant, indifferent, mocking, mournful, distraught. This unusual point of view was inspired by a small sketch in ink by 16th Century Spanish Mystic, St. John of the Cross, in which you look on the Crucified Christ, as if floating above the Cross. Imagine what emotions you might have experienced had you been a bystander at the Crucifixion.

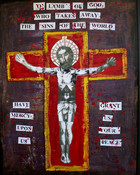

Agnus Dei may startle you, perhaps, seem a bit irreverent. I want you to do a double take and really look at the figure on the Cross. This image is a far cry from “prettified” presentations of the Crucified Christ, which became the norm in European sacred art, after Renaissance artists rediscovered the human body and perfection of form came to be associated with holiness. In fact, it is a composite collage, made from artistic representations of the Crucifixion from the medieval to modern period. The head is by French Artist Georges Rouault, the hands are by German Expressionists Otto Dix and Emil Nolde, the upper torso by Michelangelo, the lower torso by 20th century British Artist Graham Sutherland, the loins by Italian Renaissance Painter Giovanni Bellini, the knees from the magnificent 16th Century Isenheim altarpiece by the German artist, Matthias Grunewald, the feet from a medieval Spanish polychrome sculpture (artist unknown), and the halo from a contemporary Ethiopian cross.

The next series of images explores how the sign of the Cross has served as a Christian witness down the ages. Signs & Symbols shows some Early Christian representations of the cross, including the Anchor Cross, the Cross and Orb, and the Armenian “Tree of Life” Cross. Look, as well, for other traditional early Christian emblems: the sign of the fish (“fish” in Greek is an acronym of Jesus Christ, Son of God, Savior), ICXC, the Greek abbreviation for Jesus Christ, and Alpha and Omega, the first and last letters of the Greek alphabet (see Revelations 1:8.) These signs and symbols have been painted as a stylized mosaic wall, a form of Early Christian art, brought to perfection in the Byzantine era.

When the Pharisees told Jesus during his Triumphal Entry into Jerusalem to tell his cheering followers to quiet down, he replied: “If these were silent, the stones would shout out (Luke 19:40 RSV)." I had a sense of what it means for stones to speak, while looking at the decorations on Early Christian sarcophagi in the Basilica of St. Apollinaire outside Ravenna, Italy. These were moving reminders in marble of the Christian belief in the death and resurrection of Christ and the life to come. St. Apollinaire tomb engravings of a cross with Alpha and Omega signs and a dove, hovering over a baptismal fount, were the inspiration for Alpha & Omega Cross and Descent of the Dove. Coptic Cross copies a cross of Coptic design, etched into a dome on the roof of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem. To create these white and rose colored collages, I glued crumpled brown wrapping paper to wooden panels, using heavy layers of granular paint to suggest a background of unpolished stone.

Jerusalem’s Church of the Holy Sepulcher is absolutely full of talking stones, bearing witness to the faith of countless anonymous pilgrims who visited the shrine and left their mark. All down the walls of a stairwell from the main sanctuary to the Armenian Chapel one level below you can see hundreds of tiny crosses, carved row upon row into the rough, discolored stonework. There are Coptic crosses, Armenian crosses, Crusader crosses, and Maltese crosses. Some are mere scratches. Others are lop-sided. Take a closer look, now, at these wall etchings in Jerusalem Crosses Triptych. How would you have made your mark?

The Vision of St. Francis commemorates a moment, when the contemplation of an image of the Cross actually turned the Christian world upside down! In 1205, Francis of Assisi was praying before a 12th century icon of the Crucifixion in the derelict Chapel of San Damiano, just outside his hometown of Assisi, when he heard the voice of the Crucified Christ, telling him to “Go, Francis, and repair my church, which you see, is falling into ruins.” Francis took the message literally, at first, and set about fixing the San Damiano Chapel. His zeal to live an authentic Christian life would eventually “repair” the entire medieval Roman Catholic Church through the founding of the Franciscan order. This collage incorporates an image of the miraculous San Damiano crucifix in the very center. The kneeling St. Francis, to the left, comes from a fresco of The Miracle of the Crucifix, attributed to Giotto, in the Basilica of St. Francis in Assisi.

This brief meditation ends with Take Up Your Cross, a collage, which pays tribute to the Hill of Crosses in Siauliai, Lithuania, a most unusual pilgrimage site, where the faithful leave crosses of every conceivable shape, size and material in huge heaps. Although the tradition of placing crosses at Siauliai may date back to the Middle Ages, this unique form of Christian witness found special expression during the Soviet era, when the Lithuanian Roman Catholic Church suffered persecution. The former Communist regime bulldozed the site at least three times, covering it over with sewage and trash, but crosses kept appearing, as if growing out from the earth. Making this piece, I imagined Lithuanian believers in the thousands carrying their crosses to Siauliai and recalled Jesus’s words in Matthew 16:24 (NIV): “If anyone would come after me, he must deny himself and take up his cross and follow me.”

Like the crosses in this collage and at Siauliai, our crosses must surely be as unique as we are as people--each one just fitting the hollows of our shoulders and as heavy as we have the strength to bear. You have seen images of the Cross in multiple forms throughout this meditation. As you exit this website page, give some thought whether you, too, are willing to take up your cross.

From The Holy Bible: New International Version [NIV] (New York Bible Society International: 1973)