Introduction: Following the Way of Sorrow

The Resurrection of Jesus is the cornerstone event of the Christian faith, but as all believers know, Easter Sunday follows after Good Friday. The Apostle Paul’s letters to the first Christian communities stress the importance of Christ’s sacrificial death on the Cross. He tells the Corinthian Church, in no uncertain terms: “We preach Christ crucified (I Corinthians 1: 23, NIV).” In Philippians 3:10-11 (NIV), Paul says: “I want to know Christ and the power of his resurrection and the fellowship of sharing in his sufferings, becoming like him in his death, and so, somehow, to attain to the resurrection of the dead.”

This desire to identify with Christ in his suffering and death in order to understand the fullness of his resurrection is at the heart of the devotional practice of meditating on the Stations of the Cross. We know from the travel journal of Egeria, a 4th century pilgrim to the Holy Land, about a liturgical procession in Jerusalem from the Garden of Gethsemane to the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, taking place during Holy Week to remember the lasts hours of Christ. Modern pilgrims to Jerusalem follow the Via Crucis (Way of the Cross)--also known as the Via Dolorosa (Way of Sorrow)--a devotional path first marked out in the 1300s, when the Franciscan Order was placed in charge of the sacred sites of the Holy Land.

As early as the 5th century, shrines started to appear in Europe, replicating places in Palestine associated with the life and death of Jesus. They offered those unable to make the costly and perilous journey to the Middle East an alternative way to venerate the “Stations of the Cross,” a term first used by William Wey, a 13th Century English pilgrim to Jerusalem, to describe the various stops made on the Via Dolorosa to reenact the events of Good Friday.

By the 16th century, the tradition of praying at outdoor shrines commemorating Christ's Passion, was firmly established in Europe, although the number of moments to be remembered in Christ’s walk to Golgotha varied from seven “falls” to as many as 31 “stations.” The processionals moved indoors in the 17th century, and in 1731, Pope Clement XII fixed the number of stations at 14, corresponding to those now marked on the side walls of almost all Roman Catholic churches either with simple wooden crosses or more elaborate works of art.

Most of the stations are based on events in the Gospel narratives; some have evolved from time-honored stories and traditions. There is no established cycle of prayers, hymns or devotions to follow during a Stations of the Cross meditation, but whether done alone or in a group, it usually begins at the first marker, representing the Hall of Pilate, where Christ is condemned to death, and ends beside his tomb near Golgotha at the fourteenth marker. The Resurrection is often honored, now, as a 15th Station.

To accompany the many interpretations of the Stations of the Cross in my art collection, I have written a series of reflections, which, I hope, will challenge you to look at the events of Good Friday in a different way. Each meditation begins with a passage from The Holy Bible in the King James Version (Thomas Nelson: 1976), except when I felt the meaning was better served by the more contemporary language of The Holy Bible: New International Version (New York Bible Society International: 1973), marked by (NIV). The commentaries end with a prayer.

I invite you, now, to make your own journey along the Via Dolorosa. These Stations of the Cross meditations are designed to be read in sequence, preferably in one sitting, but please stop along the way and return to them as you choose.

Carl Dixon

Detail of Station I

Detail of Station XII

Stanislaw Koguciuk

Detail of Station VI

Detail of Station XIV

Lydia Garcia

Detail of Station I

Detail of Station XIII

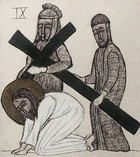

John Kohan

Detail of Station IX

Detail of Station XIV

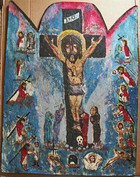

Marie Romero Cash

Detail of Station VI

Detail of Station XI

Madelene Purdie

Detail of Station IV