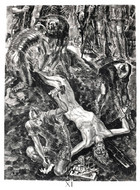

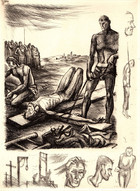

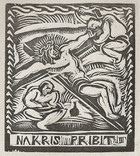

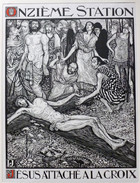

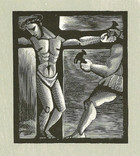

Station XI: Christ is Nailed to the Cross

For dogs have compassed me: the assembly of the wicked have enclosed me: they pierced my hands and my feet. (Psalm 22:16)

Stripped of his clothes, barely able to stand, Christ must now undergo the final torture at the Place of the Skull. His hands will be nailed to the horizontal beam he has carried with the help of Simon of Cyrene; his feet, fastened by nails to the vertical post, which supports this crossbeam. He will be hoisted into the air and die, slowly, by suffocation, as he struggles to lift his pain-wracked chest to breathe.

With each hammer blow, the metal pegs dig deeper into the skin, muscle, and bones of hands, which have touched the putrefying sores of lepers to bring healing; molded clay and spittle into a salve to give sight to the blind; held the limp, cold hand of a dead girl and restored her to life; seized a whip to drive thieving money-changers from the Temple; and broken bread to feed five thousand.

The nails pierce through feet, calloused on the countless roads he has traveled, preaching the good news of God’s Coming Kingdom. Feet that have walked on water and been washed by the tears of a penitent prostitute. Feet now caked with blood, sweat, and dust from his forced march along the Way of Sorrow.

The wounds of Christ figure prominently in the Gospel narrative of Jesus’ post-Resurrection appearances. In John 20:24-29, Jesus tells Thomas, the doubting disciple, to see for himself that he rose, bodily, from the grave and touch the very wounds in his hands and side.

When the humanity of the suffering Jesus became a focus of worship in the medieval church, special reverence was paid to these Five Wounds of Christ (two in his hands and two in his feet from the nails, and a fifth from the lance that pierced his side). Saint Francis of Assisi, who wanted to imitate Christ in all things, actually received the marks of Jesus’ wounds on his own hands, feet, and side, while praying on retreat in 1224. This first recorded incident of the appearance of stigmata has been repeated enough times in succeeding centuries to set the most skeptical materialists, searching for psychosomatic explanations.

Many modern Christians consider contemplation of the wounds of Christ as excessively morbid and would just as soon purge their songbooks of hymns, referring to the blood of Jesus. Maybe, we need to take a different look at such, seemingly, outmoded and offensive devotional practices in the light of contemporary culture. When secular society can’t seem to get enough of blood-and-guts spectacles, the Church needs to speak directly to this cult of senseless violence, drawing from its own teachings and traditions about the sacrificial death of Christ.

We should never be squeamish, contemplating the wounds of Jesus. In willingly embracing pain, suffering, and death, this bruised, battered, and, yes, bleeding Christ, became the very means of broken humanity’s redemption and reconciliation to God. We do well to remember, in the words of I Peter 2:24 (NIV), that “by his wounds you have been healed.”

In a world torn apart by hatred and violence, make me ever mindful of your wounded, bleeding, and redeeming love. Amen.

Albert Decaris

Jean Marchand

Andre Collot

Unknown Czech artist

Elisabeth de la Mauviniere

Marie Romero Cash

Adrian Wiszniewski

Louis Jou

Master of the Stalag VI D Stations

Peter Howson

Paul Aizpiri

Arthur Kemp

Pedro Cansaya

Pat M. Mallinson (Allman-Smith)

Charles Aldrich

Frank Brangwyn

Michael Vargas

Eric Gill

Bernard Brussel-Smith

Roman Sledz

Unknown Mexican Artist

Maurice Denis

Frank Brangwyn