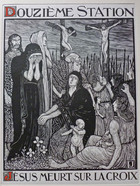

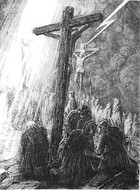

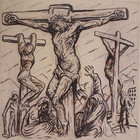

Station XII: Christ is Crucified

Your attitude should be the same as that of Christ Jesus:

Who being in very nature God,

did not consider equality with God

something to be grasped,

but made himself nothing,

taking the very nature of a servant,

being made in human likeness.

And being found in appearance as a man,

he humbled himself

and became obedient to death--

even death on a cross.

(Philippians 2: 5-8, NIV)

We have grown far too comfortable with the Crucifixion. There is little to evoke feelings of shock or shame in anodyne images of a suffering Christ, swooning on the cross in an immaculately white, starched loin cloth. The perfectly proportioned alabaster body, hanging on church crucifixes, says more about Renaissance ideals of human beauty than the grim realities of a horrific form of capital punishment. We have stylized, customized, prettified, and miniaturized Christ on the Cross, so we can wear him as costume jewelry.

I wonder, how church-goers would react if their altar paintings showed the sharpened blade of a guillotine, severing head from body; their sculptures, a writhing figure in an electric chair; and those pendants, dangling from their necks, a noose and gallows.

The Apostle Paul was well aware that preaching about the Son of God, dying a criminal’s death to save the world, was a scandal to listeners in his day. In his first letter to the Christian community in Corinth, Paul describes the Crucified Christ as “a stumbling block” to Jews and “foolishness” to the Greeks (I Corinthians 1:23).

In Jewish eyes, anyone put to death by “hanging on a tree” had to be “accursed of God” (Deuteronomy 21:23). Greeks and Romans, on the other hand, could make no sense of the bizarre notion that a divine being would willingly subject himself to the most horrific form of execution, then known, associated with slaves, traitors, and the criminal classes. As Theologian Martin Hengel writes in his illuminating little book, Crucifixion: “To assert that God himself accepted death in the form of a crucified Jewish manual laborer from Galilee in order to break the power of death and bring salvation to all men could only seem folly and madness to men of ancient times.”

What God did for humankind in the death of Christ is summed up in the Greek word, kenosis, meaning “emptying out.” The words of the ancient hymn, above, quoted in Paul’s letter to the church in Philippi, describe in poetic terms how the wondrous event took place. Though equal to God, Christ emptied himself of all his godly attributes to take on the limitations of human existence, assuming the humble role of a servant, who demeaned himself even further by accepting the most degrading and vile form of death imaginable, execution by crucifixion.

The reason for this? God’s boundless love for wayward humanity. No wonder Paul could state with such confidence that preaching about the Cross might be foolish to some, but to those who believed it was the very “power of God.” If that doesn’t shake you up, it should.

As you make your way through these meditations, this might be a good time to stay awhile longer at the foot of the Cross, as Christ gives up his ghost with the loud cry: “Father into thy hands I commend my spirit (Luke 23:46).”

When I survey the wondrous cross on which you died, help me both to receive and to share your love, so amazing, so divine. Amen.

Albert Decaris

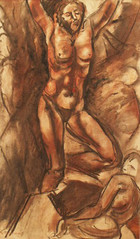

Jean Marchand

Andre Collot

Unknown Czech artist

Elisabeth de la Mauviniere

Marie Romero Cash

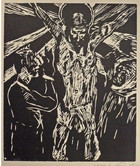

Max Thalmann

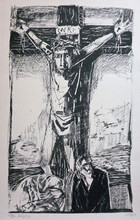

Gustav Schmidt

Mavis Budd

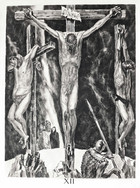

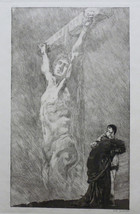

Willy Jaeckel

Adrian Wiszniewski

Louis Jou

Master of the Stalag VI D Stations

Arthur Kemp

Peter Howson

Maurice Denis

Jean Frelaut

Arthur O. Scott

Earl Stetson Crawford

Amaro Francisco Borges

Pat M. Mallinson (Allman-Smith)

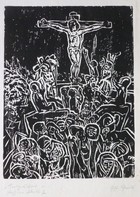

Peter Howson

Eugene Higgins

Unknown Ex Libris Artist

Georges Rouault

Rainer Herold

Milan Entler

Edward Knippers

Leon-Ernest Drivier

Lovis Corinth

Maurice Denis

Max Klinger

Otto Dix

Norman Rubington

Jean Cocteau/Raymond Moretti

Eric Gill

Letterio Calapai

Albert Servaes

Karnig Nalbandian

Hans Thoma

Bernard Brussel-Smith

Jos Speybrouck

Alfred van Loen

Karel Musil

Tyrus Clutter