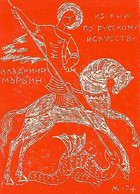

The Saintly Dragon Slayer

Who is the most popular saint? A good case can be made for George the Dragon Slayer. He is the patron of nations and peoples from England to Catalonia and Portugal to Ethiopia. He appears on horseback on the coat of arms of the Russian Federation and the Republic of Georgia and on the battle standard of the Greek Army. His red cross on a white field is incorporated into the Union Jack Flag of the United Kingdom and appears on the crests of the cities of London, Barcelona, and Genoa. He is the patron of both syphilis sufferers and the Boy Scout Movement, and he features on English pub signs and Ethiopian lager labels. Quite a spread for one saint, by George!

We are all familiar with the tale of the knight-errant on the white steed, coming to the rescue of a princess in peril who is just about to be sacrificed to a dragon, terrorizing the local citizenry. Stalwart in his faith in God, George slays the evil monster, converts the pagan state to Christianity, then, gives his reward away to the poor and/or marries the princess.

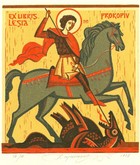

This story of George, confronting the dragon, has been the dominant subject of artistic representations of the saint down through the ages. It is, certainly, the favored theme of the modern studies of St. George in the Sacred Art Pilgrim collection, displayed here, which were created by artists and artisans from Mexico, Canada, the U.S., Russia, Lithuania, Ethiopia and other nations where his tale of valor has held sway.

Monster-slaying sagas have deep mythological roots in world civilizations (except among the Chinese who view dragons as symbols of power and prosperity). In Babylonian creation myths, Marduk, the chief imperial deity, slaughters the sea-goddess dragon, Tiamat, and creates the heavens and the earth from the halves of her body. Egyptians believed the Sun God Ra struggled in the dark hours with the serpent-dragon Apep to bring his barge safely through the Underworld. In Norse sagas, the God Thor battles Jormungandr, a sea serpent so large it could encircle the world and grab its own tail.

Greek mythology abounds in evil creature killings. Jason slays a dragon to win the Golden Fleece; Heracles decapitates the many-headed Hydra; and Perseus rescues Andromeda from a sea monster in the myth most closely resembling the legend of St. George and the Princess.

The embattled dragon motif seems to have come out of Eastern Orthodox iconography of St. George from the 10th-11th centuries, and there are other examples of to be found of Christian dragon-killing imagery. Icons of St. Theodore, a 3rd century martyr-warrior, depict almost identical scenes. Dragons figure, most famously, on the receiving end of the sword of the Archangel Michael in depictions of the “war in heaven” described in Revelation 12:7-9, when Michael and the angels overcome a dragon, identified with Satan.

The dragon tale is a fairly late narrative strand in the hagiography of St. George and first appeared in Europe in full-blown form in Jacobus of Voraigne’s 13th century bestseller, The Golden Legend. Some scholars suggest symbolic dragons used to illustrate the struggle of good and evil in iconography may well have spawned the real scales and blood monster of popular St. George narratives.

A holy dragon-killer certainly carries the aura of victory about him, and there have been numerous battlefield sightings of St. George. He is said to have appeared in the 11th century to help Crusaders at the Siege of Antioch and lead them in scaling the walls of Jerusalem. He was also a frequent combatant on the side of Christians in their battles with the Moors in Spain. St. George favored the English with a visitation, when they defeated the French at Agincourt in 1415, and there are stories of British troops seeing him with a heavenly cavalry over the battlefield of Mons in 1914 during World War I.

Not that St. George is only active on behalf of Europeans. The Ethiopians attributed their victory over invading Italian colonizers at the Battle of Adwa on the feast day of St. George in 1896 to the Dragon Slayer's intercession.

There is a much older tradition about George, dating from the 5th century, which co-exists uneasily alongside our favorite view of the knight in shining armor, rescuing a damsel in distress. In the earliest accounts of the saint’s life, he is presented as a 4th century Roman military officer who willingly accepts torture and martyrdom in imitation of Christ rather than renounce his faith.

Depending on the text, George is, variously, scourged, racked, raked with hooks and claws, slashed on a wheel, burned with torches, boiled in molten lead, baked in an oven, sawn asunder, dragged by horses, crushed with millstones, poisoned (resurrected as many as three times), and, finally, decapitated. As Cultural Historian Samantha Riches tellingly points out, this laundry list of horrors places St. George more firmly in the company of female virgin martyrs than your typical warrior saint.

Sifting through the miraculous dragon and torture tales, is there anything we can say with certainty about St. George? Yes and no. He has frequently been identified with an unnamed man of high birth, mentioned in the writings of the 4th century Church Historian Eusebius, who suffered torture and martyrdom, after defying the anti-Christian edict of the Emperor Diocletian in 303. This story would fit George nicely, except for the fact that these events are set in Nicomedia in present-day Turkey far from Lydda (now Lod) in Palestine, where pilgrim narratives from the 6th to 8th century do attest to a flourishing cult associated with a specific St. George.

Pope Gelasius (who held office from 592 to 596) had little time for hagiographic flights of fantasy, but even he had to recognize there was something special about George, however dubious the stories circulating about him. He numbered George among those saints “whose names are justly reverenced among men, but whose actions are only known to God.”

That may be as far as we can go in grounding this much loved dragon fighter in historical fact. Whoever George was, whatever George did, he has become an emblem of so many things for so many faithful people he can justly be called a Saint for All Seasons.

God of hosts,

who so kindled the flame of love

in the heart of your servant George

that he bore witness to the risen Lord

by his life and by his death:

give us the same faith and power of love

that we who rejoice in his triumphs

may come to share with him the fullness of the resurrection;

through Jesus Christ our Lord.

(Anglican collect on April 23: the Festival of George, Martyr, Patron of England, c. 304)

Suggested readings: Giles Morgan, St. George (Charwell Books, Inc.: 2006); Samantha Riches, St. George: Hero, Martyr, Myth (Sutton Publishing: 2000)

Konstantin Kalynovych

Petr Augustovic

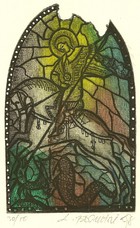

Antanas Kmieliauskas

Petro Prokopiv

Antanas Kmieliauskas

Pavel Hlavaty

Antanas Kmieliauskas

Vlastimil Kacirek

Vladimir Zuev

Leo Bednarik

Unknown Ethiopian Artist

Unknown Dutch Artist

Norman Laliberte

Karel Musil

Unknown Ethiopian Artist

Vladimir Sergeev

Lester Hines

Unknown Ethiopian Artist

Karel Benes

Nikolai Kofanov

Lucas Lorenzo

Bohdan Soroka

Unknown Ethiopian Artist